If it’s not an emergency, Blue Cross Blue Shield won’t pay……………

By Jenny Deam May 26, 2018

Starting in June, about 500,000 Blue Cross and Blue Shield of Texas members with HMO policies – which require the use of in-network doctors except in emergencies – will need to think twice before going to an out-of-network emergency room. (Dreamstime)

It’s the middle of the night and that nagging chest pressure seems to be getting worse. Could be a heart attack. Could be indigestion from the bad burrito at dinner.

Do you a) Go to the nearest emergency room; b) Find an open urgent care clinic; or c) Take a Tums and wait until morning to see your doctor during office hours?

Choose wisely, Texans, because the stakes are about to get a whole lot higher.

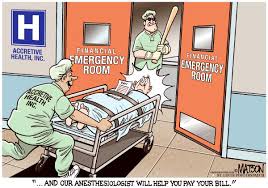

Starting June 4, Blue Cross and Blue Shield of Texas, the state’s largest insurer, will step up its scrutiny of all out-of-network emergency room claims for patients who have health maintenance organization, or HMO, plans. If, after treatment, a company review finds patients could have reasonably gone elsewhere for care, it will pay zero.

That means even insured patients could potentially be on the hook for thousands — if not tens of thousands — of dollars in medical bills if they make the wrong choice.

As word of the new initiative seeped out, doctors across the state were swift in their outrage and accused Blue Cross Blue Shield of forcing frightened patients to self-diagnose when they are at their most vulnerable. Guessing wrong, the doctors contend, could be deadly.

Blue Cross and Blue Shield flatly denies putting customers at risk.

“One thing I want to make very clear right off the start is if any of our members, or quite frankly, anybody in general, if you have or think you have a medical emergency you need to seek treatment at the closest place you can that can provide needed treatment or call 911,” said Dr. Robert Morrow, president of the Houston and Southeast Texas office of Blue Cross and Blue Shield of Texas.

Instead, the after-the-fact review and potential for denials can help weed out people inappropriately using expensive emergency rooms for non-emergencies. The insurer also seeks to push back against inaccurate billing, overtreatment and “excessive and unconscionable charges” from the physicians who treat emergency patients, Morrow said in an interview with the Houston Chronicle.

“We have, quite frankly, identified quite a bit of fraud, waste and abuse that happens within the context of some of these treatments at some of these facilities,” he said.

The Texas Association of Health Plans has previously said its internal claims data shows that nearly half of emergency physician claims in 2015 were outside the networks of the state’s three major insurers: Blue Cross and Blue Shield of Texas, Aetna and UnitedHealthcare. Doctors outside a network are free to bill two to three times more than those within network coverage, the health insurance lobby’s data showed.

RELATED: Patients squeezed in feud between docs, insurance companies

In the example of chest pains, Morrow said his company would review the circumstances but most likely pay the claim even if it is out of network.

The ‘prudent layperson’

HMO plans already sharply restrict members seeking out-of-network services, typically not paying for care. The legal exception has always been if a patient truly believes they are having an emergency. In such cases the insurer must cover out-of-network screenings, tests and treatment, according to the Texas Department of Insurance.

A piece of legalese buried in most state insurance codes and in the federal Affordable Care Act is called the “prudent layperson” standard, and that is what’s at the heart of this fight, both in Texas and across the country where other insurers are trying similar measures. Does a patient think they are in crisis?

In Texas about a half-million people have Blue Cross Blue Shield HMO plans. It is not immediately known how many in Houston, the company said.

Morrow, who previously practiced family medicine, said his company will not penalize a patient if the ultimate diagnosis rules out an emergency — a stomach bug rather than appendicitis, for instance.

Instead the measure seeks to look at patient intent, of “what brought them in,” he said. Morrow calls it a “well thought-out” remedy to a stubborn problem.

Emergency room doctors call it something else entirely.

“This is a war going on,” said Dr. Cedric Dark, an emergency physician at Ben Taub Hospital and CHI St. Luke’s Health and a health scholar at Baylor College of Medicine Center for Medical Ethics and Health Policy.

RELATED: Surprise bills in store for many Texas ER patients

Dark accuses Blue Cross and Blue Shield of circumventing the prudent layperson rule in an effort to underpay doctors and enrich the company. Doctors and the insurance industry have been locked in an escalating fight over reimbursement insurance for years. Dark says this is just the latest volley.

Morrow counters that his company’s policy adheres to the prudent layperson standard and in fact “embraces it.” He also points to Blue Cross and Blue Shield’s efforts to educate members on what constitutes an emergency.

Still, the Texas Department of Insurance was concerned enough to send a letter May 9 to the insurance company asking for clarification.

“The review is performed to determine if the claim accurately reflects the services rendered according to the medical records, and if the medical record supports the determination that an emergency existed in accordance with the prudent layperson standard in the Insurance Code,” Dr. Dan McCoy, Blue Cross and Blue Shield president, replied in a May 17 letter.

McCoy’s letter, obtained by the Chronicle through a records request, added that “HMO members will have their appeal rights if they disagree with the decision that their visit was not an emergency.”

Emergency room doctors argue it is wrong to try to divine patient intent in retrospect.

“Why do people come to an emergency room? Because they are afraid. They don’t know what to do. It’s the mom who brings in her child at 2 a.m. because a fever is spiking,” said Dr. Carrie de Moor, CEO of Code 3 Emergency Partners, a Frisco-based network of free-standing emergency rooms, urgent care clinics and a telemedicine program.

“They are Monday morning quarterbacking,” said de Moor. “The physicians who are reviewing records are not laypersons.”

A trained doctor might look at the circumstances of a case after the fact and see it differently than a patient or doctor in the heat of the moment, she said. In addition, a doctor might need to perform a battery of costly tests to arrive at the correct diagnosis or rule out more serious ones.

De Moor said what’s really at play is the insurer taking aim at the proliferation of free-standing emergency rooms. The retail centers, equipped and staffed like a hospital emergency room, are a Texas phenomenon that is starting to spread in a handful of states across the nation. De Moor is chair of the American College of Emergency Physicians’ section on Freestanding Emergency Centers.

Patients are often confused by free-standing emergency rooms and their less expensive cousin, urgent care clinics. Often the two care centers are close to each other and sometimes even in the same facility. One big difference between the two, however, is that free-standing emergency rooms typically are not included in patient insurance coverage.

‘Land mines’ for patients

Morrow of Blue Cross and Blue Shield of Texas acknowledges the bitter feud between his company and the free-standing emergency room industry but lays the blame at the provider’s doorstep. He pointed to a $45,000 bill to treat a patient who came into the emergency room with a sore throat, later diagnosed as tonsillitis.

RELATED: Confusion over medical facilities could cost a bundle

Currently, about 80 percent of Blue Cross and Blue Shield out-of-network claims for emergency care come from free-standing emergency rooms, according to insurance claims data.

Stacey Pogue, a senior policy analyst for the Center for Public Policy Priorities in Austin, is wary of the new initiative.

“I can see why they are doing this,” she said of the unsustainable trajectory of health care costs. But the test will come in how it is implemented — and how well the appeal process works, she said.

Pogue and other health policy watchers worry most about how patients could get stuck in the crossfire. If their insurer decides to deny payment to the doctor or facility, the entire bill could then get passed on to the patient with a demand for payment. And unlike in other types of insurance plans, HMO coverage is not eligible for the state-sponsored mediation process.

“There are land mines all over this,” she said.

The Blue Cross and Blue Shield rollout is not happening in a vacuum. Elsewhere in the country, Anthem, the insurance giant, has initiated a similar program in six states — Kentucky, Missouri, Indiana, Ohio, New Hampshire and Connecticut. In the Anthem program, the final diagnosis can be part of the denial decision.

Anthem has faced harsh criticism from emergency room physicians and some health policy experts who worry about a chilling effect among patients trying to decide when and where to get emergency care.

The insurer denied thousands more emergency room claims last year over the previous year, according to an analysis of claims by the American College of Emergency Physicians. The spike corresponds with the implementation of Anthem’s program, said Laura Wooster, associate executive director of public affairs for the physicians organization.

While not identical to Anthem’s program, she said her organization is still concerned about what could happen in Texas.

“You can’t look at intention in a medical record. At best, you can look at presenting symptoms,” she said. Mostly she worries people may skip care and then something goes wrong. “Will you ever be able to forgive yourself?”

jenny.deam@chron.com