“One day, a group of villagers was working in the fields by a river. Suddenly someone noticed a baby floating down the river………….”

By Dave Chase

Hospital CEOs behave similarly to chain hotel general managers due to perverse incentives, with their primary task being to fill beds and answer to distant financial overlords. As a result, they create/manage the culture represented in this tale.

In an earlier piece, I propose a different paradigm where hospitals are the fire department of our health. There is an accompanying issue that most communities have, unwittingly, let themselves be colonized by Wall Street driven organizations (e.g., publicly traded hospitals/carriers/PBMs or even tax-exempt hospitals growing their ever-larger bonds to fuel more “baby-saving” to use the parable below.

The origins of this parable are unknown.

The Parable of the River

One day, a group of villagers was working in the fields by a river. Suddenly someone noticed a baby floating down the river. A woman rushed out and rescued the baby, brought it to shore and cared for it. During the next several days, more babies were found floating downstream, and the villagers rescued them as well. But before long there was a steady stream of babies floating downstream. Soon the whole village was involved in the many tasks of the rescue work: pulling these poor children out of their stream, ensuring they were properly fed, clothed, and housed, and integrating them into the life of the village. While not all the babies, now very numerous, could be saved, the villagers felt they were doing well to save as many as they did.

Before long, however, the village became exhausted with all this rescue work. Some villagers suggested they go upstream to discover how all these babies were getting into the river in the first place. Had a mysterious illness stricken these poor children? Had the shoreline been made unsafe by an earthquake? Was some hateful person throwing them in deliberately? Was an even more exhausted village upstream abandoning them out of hopelessness?

A huge controversy erupted in the village. One group argued that every possible hand was needed to save the babies since they were barely keeping up with the current flow. The other group argued that if they found out how those babies were getting in the water further upstream, they could repair the situation up there and that would save all the babies and eliminate the need for those costly rescue operations downstream.

“Don’t you see,” cried some, “if we find out how they’re getting in the river, we can stop the problem, and no babies will drown? By going upstream, we can eliminate the cause of the problem!”

“But it’s too risky,“ said the Village elders. “It might fail. It’s not for us to change the system. And besides, how would we occupy ourselves if we no longer had to do this?“

To pick up on the river metaphor, every community has a river of healthcare money that flows through it. For example, a community/county with 250,000 people spends $3.37 billion every year. Often the headwaters of that river of healthcare money is the community itself. Healthcare is a fundamentally local service (what’s more “local” than an interaction with a doctor/nurse?!) yet well over $1 billion river of healthcare money is diverted to Wall Street (i.e., extracted out of the local economy) each year.

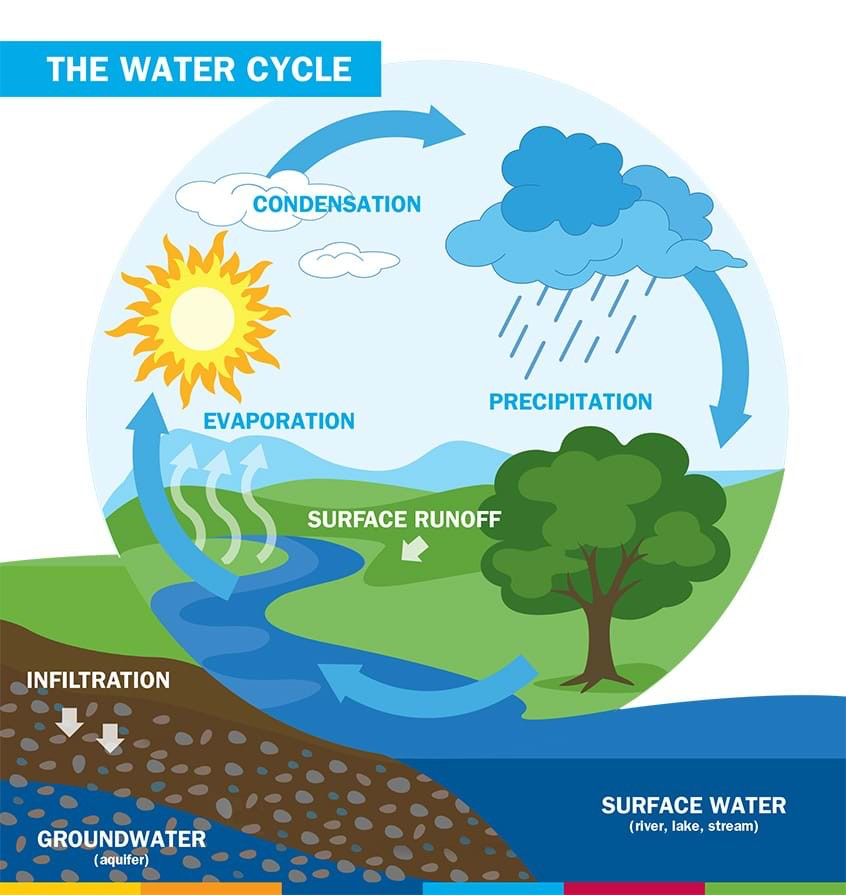

This river of healthcare money should work more like a water cycle restoring community health. This is a core element of community-owned health plans. The vast majority of hospitalizations are avoidable when the focus shifts to upstream prevention. In the old model, hospital-employed primary care physicians are “referralists” as their success is measured by how much they refer internally. In contrast, as Rishi Manchanda, MD outlined in his TED Talk, modern primary care physicians are “upstreamists.” From the Nuka model in southcentral Alaska to the Qulturum model to the Health Rosetta model in northeast Ohio and central Florida, when hospitalizations are avoided, there are vast sums of money that the community can invest in the social determinants of health such as education, healthy food and much more.