By Paul Milller, London Market Insurance

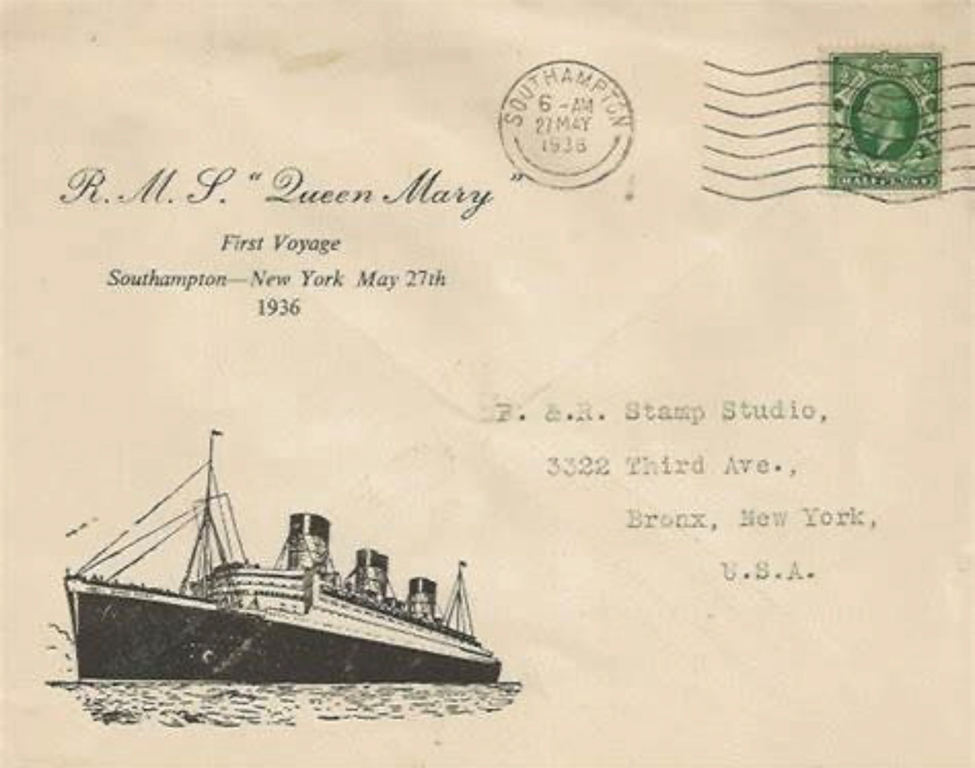

In April, 1936, a piece of paper was passed around the Underwriting Room at Lloyd’s of London bearing at the top the notation “Queen Mary — £4,800,000”.

Each underwriter wrote down his name and a figure representing the share of insurance on the new ship that he was willing to assume. When the last man had subscribed, the figure totalled £3,000,000. The Government assumed the remaining £1,800,000 of the risk and the new liner was permitted to be put out to sea. British Pride dictated that British men should carry all the insurance on the liner, so what the market could not absorb was underwritten by the treasury.

A year earlier, the company charged with building the Golden Gate bridge started work. Their first task was to apply for $38,000,000 insurance. Bonds sold to build the bridge would be collected at tolls from those who used it. Should the bridge have collapsed, there would be no tolls and no money to retire the bonds. Therefore, insurance against that risk was the first step in building the bridge. The insurance also protected the bridge’s construction commission against loss or damage from fire, lightning, flood, rising waters, ice, explosions, earthquake, tornadoes, windstorms, collisions, strikes, riots and public commotion.

Construction workers also had to be covered under California state workmen’s compensation law against accident or death. The premium of this coverage was $22.51 for every $100 of payroll. The contractor charged with building the bridge also had to take out public liability coverage. Part of it was built over land, where rivets or steel beams might fall on passers-by. To keep down such claims, the bridge engineers spent $82,000 for the biggest safety net ever woven.

The huge insurance coverage required for a structure such as the Golden Gate had to be split amongst several insurers – in the same way that the Queen Mary was insured at Lloyd’s. On federal projects at the time, no one company was allowed to insure a portion of a risk greater than 10% of its combined capital and surplus, which fixed a limit of about $1,500,000 on the largest amount any one American company could carry. Casualty companies at the time would typically divide a contract into tenths, spreading the risk amongst ten companies.

The largest policy in the United States (up to that point) that was underwritten in this fashion was put together in 1935. That year, the S.S. President Roosevelt arrived in New York Harbor with a shoebox sized package locked in its safe. Had anything happened to that package, American insurers would have been $2,000,000 out of pocket. It contained the 726 carat Jonker diamond, which at the time was the fourth largest stone in diamond history.