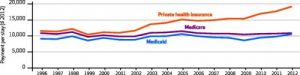

“As recently as 2000, private payers were paying only 10% more than Medicare. Since then, the gap has been growing by leaps and bounds.” That has since grown to 200-300% and as much as 400%……….

Why Employers Pay Too Much For Health Care

John C. Goodman Contributor

PolicyI offer market-based healthcare solutions.

Employers make four mistakes when they select insurance for their workers.

Did you know that employers are paying hospitals more than twice as much as what Medicare pays? At some hospitals they are paying four times as much. Those are the findings from a new study by the RAND Corporation.

It wasn’t always so. In fact, as recently as 2000, private payers were paying only 10% more than Medicare. Since then, the gap has been growing by leaps and bounds.

It wasn’t always so. In fact, as recently as 2000, private payers were paying only 10% more than Medicare. Since then, the gap has been growing by leaps and bounds.

What makes this especially surprising is that it has happened at a time when employers have been getting increasingly aggressive about controlling health care costs.

So, what’s going wrong? And who’s to blame? In my opinion, employers are to blame.

A few employers are smart buyers of care. Rosen Hotels & Resorts in Orlando, for example, is spending from one-half to two-thirds of what other employers typically spend. By contrast, most employers are making four big mistakes.

Before getting to that, let’s dispense with a misconception that is popular both on the political left and in the business community. That’s the idea that because the federal government is such a large buyer of care it can force hospitals to cough up large discounts that an ordinary employer has no hope of negotiating.

If that notion sounds sensible to you, consider that thousands of Canadians come to the United States every year for medical care – often because they are tired of waiting for care in their home country. For such big-ticket items as hip and knee replacements these individuals (foreigners no less, without any government or employer bargaining for them) manage to pay prices similar to what Medicare pays.

Canadians use agencies to help them connect with providers. But these agencies don’t discriminate. Whatever the Canadians are doing you and I can do as well.

Medibid is another service I have described before. It facilitates transactions between doctors and patients online. Last year the firm facilitated 7,575 transactions resulting in almost $75 million in billed charges. In almost all cases, the fees patients pay are equal to Medicare rates – or even less.

But you may be thinking: is this something employers can do? Indeed, it is. Empowering employees with money and letting them negotiate on their own may be far more effective than anything the employer is likely to achieve.

Several years ago, the health insurer Anthem discovered that the charges for hip and knee replacements in California were all over the map, ranging from $15,000 to $110,000. Yet there were 46 hospitals that routinely averaged $30,000 or less. So, Anthem entered an agreement with CalPERS (the health plan for California state employees, retirees and their families) to pay for these procedures in a different way.

Patients were encouraged to go to one of the 46 hospitals. They were free to go elsewhere, but they were told in advance that Anthem would pay no more than $30,000 for a joint replacement.

The result: although 30 percent of the enrollees went to “out-of-network” hospitals, the cost of care at these hospitals was cut by one-third in the first year and quickly fell below the $30,000 benchmark.

Think about that. The insurer made no phone calls. Sent no letters. There was no bargaining. No discussions whatever. Employees were sent into the medical marketplace knowing they only had so much money to spend. And voilà! Prices came down.

So, what is the typical employer doing wrong? Ignoring four principles. One of them I learned from the president. The other three I learned from people I have worked with.

The Donald Trump Principle: “Be prepared to walk away from the table.”

Before there was ObamaCare, executives of Blue Cross of Texas told me their basic employer plan included every single hospital in the Dallas Fort/Worth area – no matter how poor the quality or how high the cost. (At last count there were 83 of them.)

When Blue Cross entered the ObamaCare exchange, it offered similar plans and the result was disastrous. By some estimates, the insurer lost more than a billion dollars before it changed course.

The most successful Obamacare insurer in the country is Centene – which has captured almost one-fifth of the entire market, nationwide. Centene started out as a Medicaid contractor. The private plans it offers in the individual market look like Medicaid with a high deductible. (In most places, Medicaid rates are about 10% less than Medicare.)

If a doctor or hospital refuses to accept Centene’s low fees, they are excluded from the Centene network.

Any health insurer that is still surviving in the individual market is likely following Centene’s example. That means you cannot buy individual insurance in Dallas that includes UT Southwestern – probably the best medical research facility in the world. You can’t buy individual insurance in Texas that includes MD Anderson in Houston, one of the top cancer treatment facilities in the country.

But employers need not follow in Centene’s footsteps and they don’t have to live with the perverse incentives Obamacare has created for individual insurance. Ideally, they should aim for a network of providers that are both low-cost and high-quality.

The individual market shows conclusively that private buyers can lower their costs a lot if they are willing to say “no” to some providers.

The John Von Kannon Principle: “Have airline ticket, will travel.”

Which hospitals are giving Canadians and MediBid patients 50% off? One could easily be a hospital right next door to you. Hospitals are willing to give traveling patients deals that they won’t give those of us who live nearby. The reason? Hospitals believe that if you live in their neighborhood, they’re going to get your business, regardless.

The “medical tourism market,” as it’s sometimes called, has three requirements: (1) you have to be willing to travel and (2) you have to pay up front, and (3) there can be no insurance company interference after the fact.

John Von Kannon was for many years treasurer of the Heritage Foundation and probably the best fundraiser for right-of-center causes in the country. His theory of successful fundraising: you must travel to see the donors.

Eventually hospital competition will come to your neighborhood. For the time being, the Von Kannon principle applies to health care as well as to fundraising.

The Gerald Musgrave Principle: “Economizing must benefit the economizers.”

Health City Cayman Islands attracts patients from all over the Caribbean, from Central and South America and from the United States. The cost is similar to what Medicare pays. The quality appears to be better than what is typical in the U.S. So why aren’t more employers taking advantage of it?

Some employers have tried medical travel by offering to waive the deductible for the employee. That means the employee saves, say, $1,000 so that the employer can save $15,000. They wonder why the employees don’t jump at the opportunity.

Dr. Musgrave was my coauthor for Patient Power, and he helped develop the idea of Health Savings Accounts. Years ago, he recognized that people don’t economize on spending in order to save money for someone else – especially their employer.

Employers should consider giving all the savings of medical travel to the employees. Every study that has ever been done on the matter has concluded that employee benefits eventually substitute dollar-for-dollar for wages. That means the reason to lower health care costs is not to save the employer money. It’s to increase employee take-home pay.

The Thomas Smith Principle: “I was never conned by someone I didn’t like.”

There is very little difference today between a garden variety non-profit hospital and one that is for profit. They do the same things. They operate the same way. Yet all too often, non-profit hospitals pose as charities. Employers are encouraged to believe that supporting these institutions is a civic duty.

Tom Smith was for many years the chairman of a think tank I started, and I learned much from his leadership. If you’re wondering if this particular principle applies in your community, check out how many executives of the non-profit hospital next door are making seven-figure salaries.

To employers who want to stop wasting money on health care, I urge you to pay attention to all four principles.

Visit the Goodman Institute and follow me on Twitter.