When people talk about expensive drugs, they usually are referring to drugs like Lipitor for high cholesterol ($1,500 a year), Zyprexa for schizophrenia ($7,000 a year) or Avastin for cancer ($50,000 a year). But none of these medicines come close to making Forbes’ exclusive survey of the most expensive medicines on the planet.

When people talk about expensive drugs, they usually are referring to drugs like Lipitor for high cholesterol ($1,500 a year), Zyprexa for schizophrenia ($7,000 a year) or Avastin for cancer ($50,000 a year). But none of these medicines come close to making Forbes’ exclusive survey of the most expensive medicines on the planet.

Alexion Pharmaceutical’s Soliris, at $409,500 a year, is the world’s single most expensive drug. This monoclonal antibody drug treats a rare disorder in which the immune system destroys red blood cells at night. The disorder, paroxysymal nocturnal hemoglobinuria (PNH), hits 8,000 Americans. Last year Soliris sales were $295 million. Since Alexion started selling Soliris two years ago, its stock price is up 130%.

In the inverted world of drug pricing, the fewer patients a drug helps, the more it costs. Before testing Soliris for PNH, Alexion tested the drug for rheumatoid arthritis, which afflicts 1 million Americans. The trials failed. But if it had worked for arthritis, Alexion would likely have had to charge a much a lower price for this use, as would have to compete against drugs that cost a mere $20,000.

Three other drugs cost more than $350,000 per year. Shire Pharmaceuticals’Elaprase ($375,000 per year) treats an ultra-rare metabolic disorder called Hunter’s syndrome. Just 500 Americans suffer from the disease, which causes infections, breathing problems and brain damage. Last year domestic sales of Elaprase were $353 million.

Naglazyme from BioMarin Pharmaceuticals treats another rare metabolic disorder and costs $365,000 a year, according to investment bank Robert W. Baird. Viropharma predicts that sales of its Cinryze, a treatment to prevent a dangerous swelling of the face, will increase from $95 million last year to $350 million several years from now. The drug costs an estimated $350,000 a year.

In Depth: The World’s Most Expensive Drugs

Unlike pills that come in standard doses, all the most expensive drugs are injected biotech drugs whose dosing varies by weight or other factors. Forbes assembled its list by interviewing biotechnology industry experts and obtaining estimates of average price per patient from the companies themselves or Wall Street analysts who cover them.

Amazingly, many brutally expensive cancer drugs don’t make the cut. Targeted cancer drugs only help a small minority of patients for a few months. This reduces their average cost. Allos Therapeutics’ Folotyn treats a rare type of lymphoma and costs $30,000 per month. But the average patient is only on the drug for just a few months, so it doesn’t make the list.

Biotech companies defend their pricing. “The high cost is to support the few patients who will ever need it,” says Alexion Chief Executive Leonard Bell. “Most people with ultra-rare disorders live without any treatment.”

Nonetheless, the price of each new rare-disease drug seems to get higher each year. It used to be that pricing a drug at $100,000 per year raised eyebrows. Now that price level has become routine.

Selling drugs for rare diseases has become immensely profitable. There are so few patients that companies don’t have to invest as heavily in marketing. The medicines usually get paid for by insurers or governments. “I’m not aware of any [insurance] plans that have looked at any of these categories and said we don’t pay for these,” says Steven Russek, a vice president at pharmacy benefits manager Medco. “They want to make sure that there is no overuse or misuse and that the patients who need them are the ones getting them and there is no waste involved.” The manufacturers give their drugs for free to uninsured patients.

The success of specialty drugs for rare diseases comes at a time when the traditional drug business of selling medicines to the masses is in decline. Medicines touted as $1 billion sellers for Eli Lilly and Bristol-Myers Squibbhave ended up with flat sales. Selling drugs for rare diseases is the future of the biotechnology industry,” says Geoffrey Porges, an analyst at Sanford C. Bernstein.

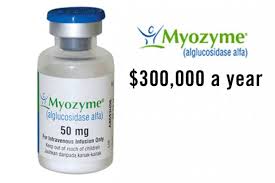

Of course, patients whose lives are saved are grateful. Mia Hanley was diagnosed with Pompe disease when she was five months old in 2005. “I didn’t know anything about Pompe disease, except that it was fatal,” says Mia’s mother, Dawn. Pompe usually kills in the first year; patients who survive need wheelchairs and ventilators. But Dawn was lucky enough to enter a clinical trial for Myozyme, the drug developed by Genzyme to treat the disease. Thanks to twice-monthly infusions of this medicine, Mia can speak, walk with leg braces and feed herself. “We are one of the lucky ones,” says Dawn.

Myozyme, which inspired the Harrison Ford movie Extraordinary Measures, costs up to $100,000 for a child. But according to Genzyme, the average cost of adult treatment is $300,000 per year. (Because of recent manufacturing snafus, most adults with the disease are currently getting an experimental version for free.) “It’s a lifesaving therapy,” says Priya Kishnani, a Duke researcher who ran clinical trials of Myozyme. “Society bears the cost for some patients that cost more.”

In Depth: The World’s Most Expensive Drugs

Specialty drugs have gotten more expensive than anyone imagined. For years drug companies ignored any disease that didn’t afflict millions of patients. That started to change in 1983 when Congress, inspired by an episode of the television show Quincy, M.D., passed a law giving an extra monopoly for drugs for orphan diseases that hit fewer than 200,000 people in the country.

Initially biotechnology firms focused on more common orphan diseases like multiple sclerosis. In 1991 Genzyme launched Ceredase for Gaucher disease, a disorder in which a missing enzyme causes lumps of fat to build up in the spleen, heart and even the brain. Ceredase, made from human placentas, replaces that enzyme and initially cost $150,000 a year. Some observers naively expected the price to drop when a new version, made in genetically engineered hamster cells, hit the market in 1994. But the new version, Cerezyme, now costs $200,000 for the average patient and has annual sales north of $1 billion.

While some patients with Gaucher disease are desperately ill, others have relatively mild symptoms. Melissa Landau Steinman, 41, a Washington, D.C., advertising lawyer, didn’t know she had Gaucher until she was five months pregnant with her first son. Her liver and spleen were enlarged, and she had to go on Cerezyme in order to could have another child. One of her children has the disease but doesn’t have symptoms.

“The most stressful part of having Gaucher has been worrying about insurance issues,” says Steinman. “It’s such an expensive drug that even though people pay for it you have to worry about things like am I going to exceed my lifetime cap? Is all that I’ve worked in my life been meaningless?”

Some competition is finally arriving to the rare disease market. Shire is waiting for the Food and Drug Administration to approve its new Gaucher’s drug and says it will price the medicine 15% less than Cerezyme. Pfizer and the Israeli biotech company Protalix, are testing a Cerezyme competitor made in carrot cells that could cost even less. Novartis is also getting into the rare disease field. The entry of big drug companies, desperate for sales, could be what finally drives down prices of these drugs.