With the lid ajar on Pandora’s box, we are likely to see employer demands pegged to price transparency and more strategies built on provider prices.

Private Payers Pay 2.7 Times on Average What Medicare Pays Hospitals

MyHealthGuide Source: Suzanne Delbanco, Ph.D., Executive Director of Catalyst for Payment Reform, “As healthcare prices are revealed, hospitals face hard choices”, Modern Healthcare.

Greater transparency has always been a source of anxiety for many healthcare industry stakeholders. When I was the founding CEO of the Leapfrog Group, verbal rotten tomatoes were often launched my way when speaking to hospital leaders about the insights into hospital quality and safety sought by employers. The argument: There is no easy, accurate and fair way to measure quality, much less report it publicly.

Over the last decade, the voice of employers seeking transparency into healthcare prices and quality has been amplified, and healthcare providers and payers have warned about unintended consequences. Among the arguments: It will lead to higher prices when low-cost providers see that the market will pay more and it will encourage patients to seek care from higher-priced providers because they equate price with quality.

At Catalyst for Payment Reform, we understand the complicated differences across charges, prices, a patient’s share of the costs and the total cost for an episode of care. But these excuses have gotten us nowhere but to a system that seems to ignore the real health and financial impact on Americans.

We know there is little relationship between healthcare prices and quality and that there is great variation in both. And now, thanks to a recent study by RAND Corp., we know which hospitals across 25 states are being paid the highest prices. Pandora’s box is open and there’s no closing it.

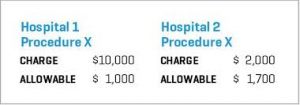

- The RAND study found that, on average, private payers are paying hospitals about 2.7 times what Medicare pays them for the same services.

Why can some hospitals charge higher prices than others? Market power.

Increasingly there is a correlation between who has the market power and what prices they can command. In the case of hospitals, market power can either be a result of market share or reputation. But given the poor correlation between quality and price, it doesn’t provide a satisfying rationale to employers and the other healthcare purchasers who cover much of the expense of healthcare services used by the 158 million Americans who get their insurance through their employer used by the 158 million Americans who get their insurance through their employer.

What are healthcare purchasers likely to do with their newfound knowledge? Steer employees and their family members away from overpriced healthcare providers through benefit design incentives or create narrow or tiered provider networks. Some purchasers have cut out coverage for particular providers. Others have pursued direct contracts with providers. And they will continue, where they can, providing quality and price information about covered providers to enrollees in their health plans. While we know few Americans regularly use such information to make healthcare choices, employers will use it in designing their healthcare benefit programs.

What are healthcare purchasers likely to do with their newfound knowledge? Steer employees and their family members away from overpriced healthcare providers through benefit design incentives or create narrow or tiered provider networks. Some purchasers have cut out coverage for particular providers. Others have pursued direct contracts with providers. And they will continue, where they can, providing quality and price information about covered providers to enrollees in their health plans. While we know few Americans regularly use such information to make healthcare choices, employers will use it in designing their healthcare benefit programs.

Hospitals have a choice about how to react to these employer-led strategies, as they did in response to the California Public Employees’ Retirement System’s now well-known reference pricing program for total joint replacements. Some hospitals made the cut due to the prices they had already agreed to; others asked to renegotiate to avoid losing patient volume.

A lot can get in the way of purchasers’ strategies. Market power sometimes gives providers leverage to refuse to share information about their quality and cost or to deny health plans the ability to steer patients away from them. Even when exposed through studies like RAND’s, they can continue to command higher than competitive prices.

The next few years are likely to test the ability of the healthcare marketplace to meet the needs of those who use and pay for care. If employer efforts continue to be thwarted, significant policy intervention could be on the way, whether federal or state, such as laws governing surprise billing and out-of-network charges or making contract terms between health plans and providers transparent.

The quest for transparency began with quality and, consequently, we now have employers who won’t consider hospitals for a high-performance network if they won’t report to the Leapfrog Group survey. With the lid ajar on Pandora’s box, we are likely to see employer demands pegged to price transparency and more strategies built on provider prices.