Insulin’s Inventor Sold the Patent for $1. Then Drug Companies Got Hold of It.

Never underestimate the greed of a pharmaceutical company.

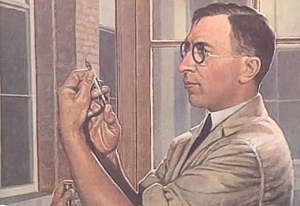

Frederick Banting wasn’t a dude who backed down. The Army refused him due to poor eyesight in 1914; in 1915, he tried again and got in. He got rejected from a Toronto hospital in 1919; he set up his own successful practice in 1920. So it’s not a surprise that Banting did what other scientists and doctors had struggled to do for decades: discovered and refined insulin therapy. His three-person team knew that this treatment was both urgently needed and incredibly tricky to get right; they wanted to make sure the public could access it, and that it was safe. So they made a move for the common good: saying that profit was not their goal, they sold the patent for insulin to the University of Toronto for just $1 each. The University then gave pharmaceutical companies the right to manufacture the drug royalty-free.

It made sense at the time; Banting and his team were worried that if they didn’t patent the drug at all, drug companies would rush to patent an inferior, possibly dangerous version and try to turn huge profits on it. The thinking seems to have been that if drug companies didn’t have to pay royalties, they would keep prices low.

The thinking was wrong. Less than thirty years later, drug manufacturer Eli Lilly and Company and two other companies were indicted for an insulin price-fixing scheme.

But that was only the beginning: in the late seventies, the process for synthetic insulin was perfected, making it far easier and less risky to produce. Since then, prices have been on a sharp uphill climb with no end in sight.

Insulin is a billion-dollar industry with zero low-priced generic versions on the market. While most name-brand drugs have generic versions that cost less than half the price, insulin is different. Miriam Tucker at Medscape explains:

Insulin’s Canadian discoverers sold the patent to their university for $1, stating that profit was not their goal. Since then, a series of incremental technological advances have maintained the patents, while older formulations have been pulled from the market. [After] identifying the glucose-lowering substance later known as insulin at the University of Toronto in 1921, Dr Frederick Banting and medical student Charles Best waited 2 years before seeking a patent and then only with the intent of publishing the extraction method, writing: “When the details of the method of preparation are published, anyone would be free to prepare the extract, but no one could secure a profitable monopoly.”

The next several decades brought successive improvements: adding protamine prolonged insulin’s action, while zinc allowed it to be combined with short-acting insulin in a form patented in 1946 under the name “neutral protamine Hagedorn (NPH),” after its Danish founder. Lente, a slower version without protamine, came along in the mid-1950s.

These advances allowed for more dose-adjustment options and also extended the patents into the 1970s. Further innovations that improved purity pushed the patents ahead another decade.

Tucker goes on to quote an article in the New England Journal of Medicine by Jeremy A Greene, MD, PhD, and Kevin R Riggs, MD, MPH: “On the whole, it’s hard to say that contemporary patients who cannot afford their insulin (let alone the patent-protected glucometers and test strips required to adjust the dose) are well served by having as their only option an agent that is marginally more effective than those that could have been generically available 50 or 30 or 10 years ago, had generics manufacturers introduced cheaper versions when patents expired.”

Greene and Riggs again:

“The drugs that ultimately see extensive generic competition differ from those that attract few, if any, manufacturers. The history of insulin highlights the limits of generic competition as a public-health framework. Nearly a century after its discovery, there is still no inexpensive supply of insulin for people living with diabetes in North America, and Americans are paying a steep price for the continued rejuvenation of this oldest of modern medicines.”

Just goes to show: never underestimate what a drug company will do to make money off the backs of researchers who only wanted to help save lives.

Written by Caitlyn McClure

Caitlyn is Chief Editor and Director of Development for Other98.