He ended up in a mental institution, where he died at the age of 47. It is believed he died from the thing he had sought to eradicate……………………….

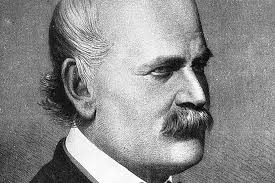

Hungarian obstetrician named Ignaz Semmelweis is considered the Father of Handwashing.

The Shockingly Recent History of People Actually Washing Their Hands

Cadavers, childbirth, and the rise of the Soap Industrial Complex all played a part in getting handwashing to catch on.

BY EMILY SOHN

APR 2, 2020

It has become a ubiquitous mantra in the time of COVID-19: Wash your hands. Cheap and easy to do, it’s one of the few pieces of advice that is essentially without controversy. And yet, hand-washing is a more recent development than you might expect, and the habit did not catch on quickly.

Instead, the shift took many decades to happen, and it occurred in the context of a variety of society-wide changes through the end of the 19th century and into the 20th. Among them: the discovery of germs, a wholesale shift in diseases theory, heavy marketing by soap manufacturers, and the rise of a scientific infrastructure that allowed researchers to document discoveries and share ideas.

In the maternity ward of the Vienna General Hospital in the 1840s, the period after childbirth was a particularly fraught time. To put it bluntly: Women were dying in droves. Regardless of their social status or how healthy they were to begin with, mothers who had recently had babies often developed a rapid heart rate, fever, shivering, and extraordinary abdominal pain that was often followed by death.

The condition, known as “childbed fever,” would sometimes occur in clusters. During epidemics, mortality rates spiked as high as 80 percent. Nobody knew why.

To get to the bottom of such high rates of postpartum mortality, a Hungarian obstetrician named Ignaz Semmelweis conducted a series of investigations that suggested patterns of transmission. Based on his observations, he proposed that doctors washing hands to save the lives of new mothers. Although few people took his advice at the time, he is often credited as the father of handwashing, which has become a mantra for staying healthy in the time of COVID-19.

The true story of Semmelweis is more complex. But his thought processes offer a window into a widescale cultural transition in the way people think about the connection between cleanliness and health.

The Vienna General Hospital had three maternity clinics operating in the 1840s. One was staffed by midwives. The other two were run by physicians. Semmelweis noticed that deaths from childbed fever, also known as puerperal fever, were much less frequent in the ward supervised solely by midwives. There, according to a history of hand hygiene published by the World Health Organization, Semmelweis found that 7 percent of new mothers died from the fever, compared with 16 percent in the doctor-led clinics.

In the 1840s, the time after childbirth was dangerous for mothers, who often contracted puerperal fever.

As he looked into those trends, Semmelweis noticed something about the doctors, says Peter Ward, a historian, emeritus professor at the University of British Columbia, and author of The Clean Body: A Modern History. Unlike the midwives, whose sole job was to deliver babies, the physicians were doing other tasks around the hospital. That included dissecting cadavers. “They didn’t wash their hands,” Ward says. “The midwives may not have washed their hands very often either, but they didn’t have the broad range of medical practice.”

In other words, the midwives were encountering and transferring fewer germs. “Germ theory,” the idea that tiny organisms get into our bodies and make us sick, had yet to take hold, and among the many hypotheses for how diseases spread at the time, one dominant idea was that diseases came from miasmas, or toxic odors emitted by decomposing organic matter. Once in the air, these “poisons” could be transmitted to people and make them sick. There was a belief that in cases of overcrowding or poor hygienic conditions, miasmas could cling to people like smoke, allowing for diseases to spread more rapidly, including from doctors to patients, says Dana Tulodziecki, PhD, a philosopher of science at Purdue University in West Lafayette, Indiana, who has written papers about Semmelweis, cholera epidemics, and 19th-century thinking on disease.

When it came to death-rate discrepancies in the Vienna maternity wards, in particular, Semmelweis considered and ruled out several competing theories, Tulodziecki wrote in a 2013 paper. To test the idea that birth position explained the difference, for example, he altered birth positions in the clinics and found no difference in mortality.

According to another hypothesis, maternal deaths were a result of psychological terror caused by a bell-ringing priest who came through one of the wards to bear last sacrament to dying mothers. But when Semmelweis sent the priest on a different route, death rates remained unchanged.

A moment of clarity came in 1847, when one of Semmelweis’ colleagues cut his finger with a scalpel during an autopsy. The wound became infected, and the doctor died. Hypothesizing that his colleague had acquired puerperal fever from the cadaver, he began requiring physicians to wash their hands with chlorinated lime after conducting autopsies. After that, mortality rate in the maternity clinic dropped to 3 percent.

A moment of clarity came in 1847, when one of Semmelweis’ colleagues cut his finger with a scalpel during an autopsy. The wound became infected, and the doctor died. Hypothesizing that his colleague had acquired puerperal fever from the cadaver, he began requiring physicians to wash their hands with chlorinated lime after conducting autopsies. After that, mortality rate in the maternity clinic dropped to 3 percent.

Semmelweis got some things right, including his idea that something external caused childbed fever: the cause would turn out to be Streptococcus bacteria. But his theories contained errors that met valid criticism, Tulodziecki says.

He proposed that the source of childhood fever came directly from cadavers, for example, which clearly wasn’t true, as childbed fever had been around longer than autopsies had. He also proposed various iterations of this theories without addressing criticisms. And his communication style was often rambling and confusing. Ultimately, his ideas—including those on handwashing—were dismissed.

That may have been hard on Semmelweis. He was committed to a mental institution, where he died at the age of 47. Although experts still debate the cause of his death, according to one hypothesis, he died from the thing he had sought to eradicate—a wound on his hand became infected, leading to sepsis.

Semmelweis was not the only person who believed in the contagiousness of disease. The idea had been around for centuries. In 1795, British obstetrician Alexander Gordon proposed that puerperal fever could be transmitted from doctors and midwives to patients. “He basically said he could foretell who the next victims would be—that when one midwife or doctor had fallen ill with childbed fever, then the chances were that the women this person would attend to next would also fall sick,” Tulodziecki says. “He’s got these really amazing tables where he traces the path of infections.”

During the Crimean War in the 1850s, the renowned British nurse, Florence Nightingale was a major proponent of handwashing. And in 1843, a few years before Semmelweis conducted his studies in the Vienna maternity wards, the Boston physician Oliver Wendell Holmes published an essay called “The Contagiousness of Puerperal Fever,” where he also proposed handwashing as a viable solution to person to person transmission.

Meanwhile, scientific methods were becoming more sophisticated. In the second half of the 19th century, scientists were beginning to use statistics, data collection, and other strategies that are now considered standard, Ward says. Simultaneously, universities in Europe and the U.S. were building up their science programs.

Within that context came a series of advances by researchers such as French biologist Louis Pasteur, who helped link microorganisms to disease; and British surgeon Joseph Lister, who pioneered the use of antiseptic in surgeries.

As doctors grappled with childbed fever and scientists developed new ways of understanding disease, cultural developments also changed the way people thought about hygiene, Ward says.

The work of Semmelweis, Pasteur, and others was simultaneous with the rise of Big Soap. In the late-19th century, Proctor & Gamble, Colgate Palmolive and other businesses launched major marketing campaigns for their soap products, primarily for use on laundry at first. Originally, soaps for body care were made by separate companies that promoted the role of soap for beauty purposes and targeted middle- and upper-class markets. And while public-health officials promoted personal hygiene for health on a smaller scale, soap companies tapped into mass-circulation newspapers and then magazines, radio and TV to spread their messages about soap’s benefits from the late-19thcentury through the middle of the 20th. Their popularization of personal hygiene and domestic cleanliness reached into all segments of society. “The soap manufacturers were zealous in promoting their products,” Ward says. “They shouted it a lot louder than the doctors did because they wanted to sell.”

Progression from Semmelweis’s time to the present has not been a steady march so much as a series of steps forward and then back. Handwashing has received spikes in attention in times of crisis like the World Wars, Ward says, when public health officials promoted handwashing as a form of people’s patriotic duty to be healthy and clean.

And although current generations wash their hands more than their predecessors, it wasn’t until the 1980s that the CDC published the first national guidelines on hand hygiene. In 1995, the CDC’s Healthcare Infection Control Practices Advisory Committee began to recommend that healthcare providers clean their hands with antimicrobial soap or a waterless antiseptic agent when they leave the rooms of patients with bacteria and other microorganisms that are resistant to medications. In 2002, guidelines added alcohol-based hand sanitizers as standard of care for keeping hands clean in healthcare settings.

In the privacy of people’s homes, too, the routine washing at multiple times throughout the day is relatively new. “It’s only within our lifetimes that the repeated habitual washing of hands has become a universal practice,” Ward says.

Scientists are also still adding new insights into what handwashing, among other hygiene practices, can and cannot accomplish. In one 2017 meta-analysis, researchers looked at 16 studies and found that hand washing with soap or hand-sanitizer was more effective than coughing etiquette (like coughing into an elbow) or wearing face masks at preventing the transmission of influenza.

One randomized controlled trial included in the analysis found that elementary-age students missed less school as a result of influenza when schools adopted hand-sanitizer routines. Another study found that influenza infection rates dropped with every 10 percent increase in adherence to hand-hygiene recommendations among healthcare workers.

Modern attitudes toward handwashing have helped stop the spread of disease.

Nobody can say how many illnesses are stopped by hand-washing, says Patrick Saunders-Hastings, an epidemiologist at Gevity Consulting, a healthcare consulting firm, and one of the authors of the meta-analysis. But the spread of disease would certainly be worse without it. “A lot of our actions are imperfect and designed to be layered one on top of the other,” he says. “So, by taking a number of semi-effective steps, we’re able to reduce the overall impact.”

In Semmelweis’ time, a dirty and bloodstained lab coat was a badge of honor, Saunders-Hastings says. And while that ethic has changed, handwashing has faced backlash in recent years. Too much cleanliness, suggests some research, has been responsible for increasing rates of allergic diseases and asthma. Even healthcare workers, studies show, aren’t all that great at washing their hands.

“Despite the protective effects of handwashing, rates of compliance, both in the public and in healthcare settings, remains low,” Saunders-Hastings says. Perhaps COVID-19 is the start of a new era in hand-washing: one where more people actually do it.