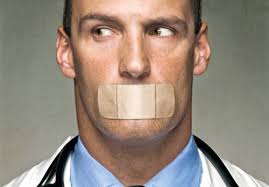

Health plans and providers often use gag clauses in their agreements and prohibit self-insured employers from using claims data for price transparency. Neither insurers nor providers want competitors and other customers to know what they are willing to settle for. However, states are increasingly outlawing gag clauses in healthcare contracts.

It’s difficult for consumers—and employers—to consider costs when making treatment decisions.

BY STEVE JACOBFROM D CEO OCTOBER 2014 ILLUSTRATION BY JONATHAN CARLSOn

Healthcare organizations are earnestly trying to help consumers shop for services. Those efforts are being met with a collective yawn.

According to a 2013 survey by Catalyst for Payment Reform, 98 percent of health plans offer cost calculator tools, but only 2 percent of members actually use them. Similarly, the Texas Hospital Association website, called Texas PricePoint, uses Texas Department of Health Services data to list what hospitals charge for common procedures. Only about 35 souls a day wander onto that site for information, according to THA vice president Lance Lunsford.

There is little doubt price transparency is a must-do for the U.S. healthcare system. One in four Americans struggled to pay medical bills in 2012, and one in 10 said they could not pay medical bills at all. A Kaiser Family Foundation study found that 70 percent of people reporting problems with medical debt were already insured. Cost-sharing was the leading contributor to the debt, as typical out-of-pocket costs were higher for health bills than the amount of cash most households had available.

Another indicator that the current system isn’t working: More than 60 percent of Americans who seek bankruptcy protection do so because of medical costs.

A recent report calculated that providing patients, physicians, employers, and policymakers more and better pricing information could save $100 billion over 10 years. The report urged physicians to embed prices for diagnostic tests in electronic health records, encouraged states to develop health claims databases to report hospital prices, and advocated requiring health plans to provide personalized out-of-pocket expense information for members.

As healthcare costs rise, employers are using a variety of cost-containment strategies, such as intensive management of high-cost patients, reference pricing, and centers of excellence for high-cost, complex services, along with wellness incentive strategies and more extensive coverage of preventive care. Price transparency is critical to many of these strategies.

Wally Gomaa, chief executive officer of Dallas-based ACAP Health Consulting, characterizes current price transparency efforts as “first generation.” The hope is that the next generation of transparency tools will show consumers quality comparisons as well as costs.

Gomaa recently spoke before a Dallas-Fort Worth Business Group on Health audience on the clear need for transparency tools. For example, hospital rates for cardiac imaging in Dallas-Fort Worth range from $1,361 to $9,219, compared with a Medicare rate of about $700. Similarly, he said, the cost of a major joint replacement ranges from $28,263 to $160,832 locally, compared with a Medicare rate of slightly more than $15,000.

Part of the problem is that listed hospital charges are not what most patients—or their insurance companies—pay. Those prices represent the starting point for negotiated rates between the hospital and insurer.

Eric Bricker, chief medical officer of Compass Professional Health Services, pointed out in a recent blog that price calculators generally do a poor job assisting consumers who face medical decisions. “Medical terminology is often too confusing to be able to know what test or procedure to correctly look up,” he wrote. “For example, is the person having an MRI of the lumbar, thoracic, or cervical spine? Is it with or without IV contrast dye? If a person is having a ‘stress test’ by a cardiologist, what type of stress test is it? There are over seven different types and they vary dramatically in terms of complexity and price.”

Making Data Available

Organizations are not deterred. The Health Care Cost Institute is one of the largest financial databases for private health insurance transactions. It is joining insurance companies Aetna, Humana, and UnitedHealthcare in developing a website that aggregates price and quality data, scheduled to launch in 2015.

The website will feature detailed cost transparency and analysis tools provided by the participating insurance companies. It may also include pricing information from other commercial health plans, as well as Medicare Advantage and Medicaid plans, depending on the state. HCCI is expecting more private insurers to join the effort before it launches.

UnitedHealthcare launched myEasyBook, an online healthcare shopping service, in Dallas and two other U.S. markets earlier this year.

The patient portal helps consumers find doctors, book appointments, and pay their share of the cost of the visits. They can search by specialty, location, or appointment date, and can compare in-network care providers.

The service is aimed at the plan members with high-deductible health plans tied to a health savings account (HSA) or a health reimbursement account (HRA). The website will calculate the cost of the appointment, the out-of-pocket costs, how much the patient has spent out of their HSA or HRA, and how much of the deductible will have been met.

States also take a stab at price transparency, but few do it well. Texas was one of seven states that received a “D” grade on price transparency on a report card prepared by CPR and Health Care Incentives Improvement Institute, a nonprofit advocacy group.

Twenty-nine states received a grade of “F.” Only two states—New Hampshire and Massachusetts—received an “A.”

A Rand Corp. study predicted that half of all U.S. workers with employer-sponsored insurance would have high-deductible plans within a decade, which could reduce annual healthcare spending by about $57 billion.

High-deductible plans encourage those with employer-sponsored insurance to become more prudent healthcare shoppers. In reality, though, consumers continue to wander aimlessly through a thicket of opaque prices, conflicting quality scores, and incomprehensible insurance documents.

‘The Neiman Marcus Effect’

In theory, transparency increases the likelihood that consumers will choose the highest-value care options and allows employers and health plans to design cost-based benefit plans.

There are several barriers to creating effective price transparency:

• Health consumers are under the mistaken impression that higher cost equates to better quality, often called “the Neiman Marcus effect.” That may be the case in most sectors of the economy, but not in healthcare. There is almost no evidence that equates cost and quality. Because of the lack of transparency, providers do their best to charge what the market will bear.

• The lack of provider competition is a disincentive to reveal pricing to consumers. Insured patients pay so little of the purchase price out-of-pocket that convenience and reputation among family and friends rank far higher than costs.

• Health plans and providers often use gag clauses in their agreements and prohibit self-insured employers from using claims data for price transparency. Neither insurers nor providers want competitors and other customers to know what they are willing to settle for. However, states are increasingly outlawing gag clauses in healthcare contracts.

• Transparency could lead to unintended consequences, prompting providers to raise prices to match those of more costly competitors.

Business Opportunity

Meanwhile, Dallas-based Compass Professional Health Services is thriving amid the chaos. The company acts as a health-system concierge for employees by seeking out the best values for specific healthcare procedures and vetting providers for cost and quality. It helps workers find in-network physicians and even sets up appointments.

Neither insurers nor providers want competitors and other customers to know what they are willing to settle for.

Compass has grown by 50 percent in the past year. It now has $29 million in annual revenue, more than 250 employees, and more than 1,750 employer clients. About a third of its clients are based in Dallas-Fort Worth.

Policyholders contact Compass directly when they want the company’s help. Scott Schoenvogel, chief executive officer, estimates about 30 percent of client employees contact Compass 2.5 times a year. A majority of the calls have to do with costs.

Schoenvogel says the increased number of price-transparency efforts has been good for business because of the issue’s exposure. He says health reform has accelerated the shift in responsibility from the employer to the employee, and the need to support workers in navigating the healthcare system.

He says about 60 percent of his clients are totally or predominantly using high-deductible health plans. More than 40 percent of companies are considering exclusively offering high-deductible plans, up from 15 percent that do today.

“Healthcare pricing and navigation are very complex,” Schoenvogel says. “There are a tremendous number of options. It takes a certain amount of experience to navigate the system with confidence. We try to build employee confidence to build a confident consumer.”